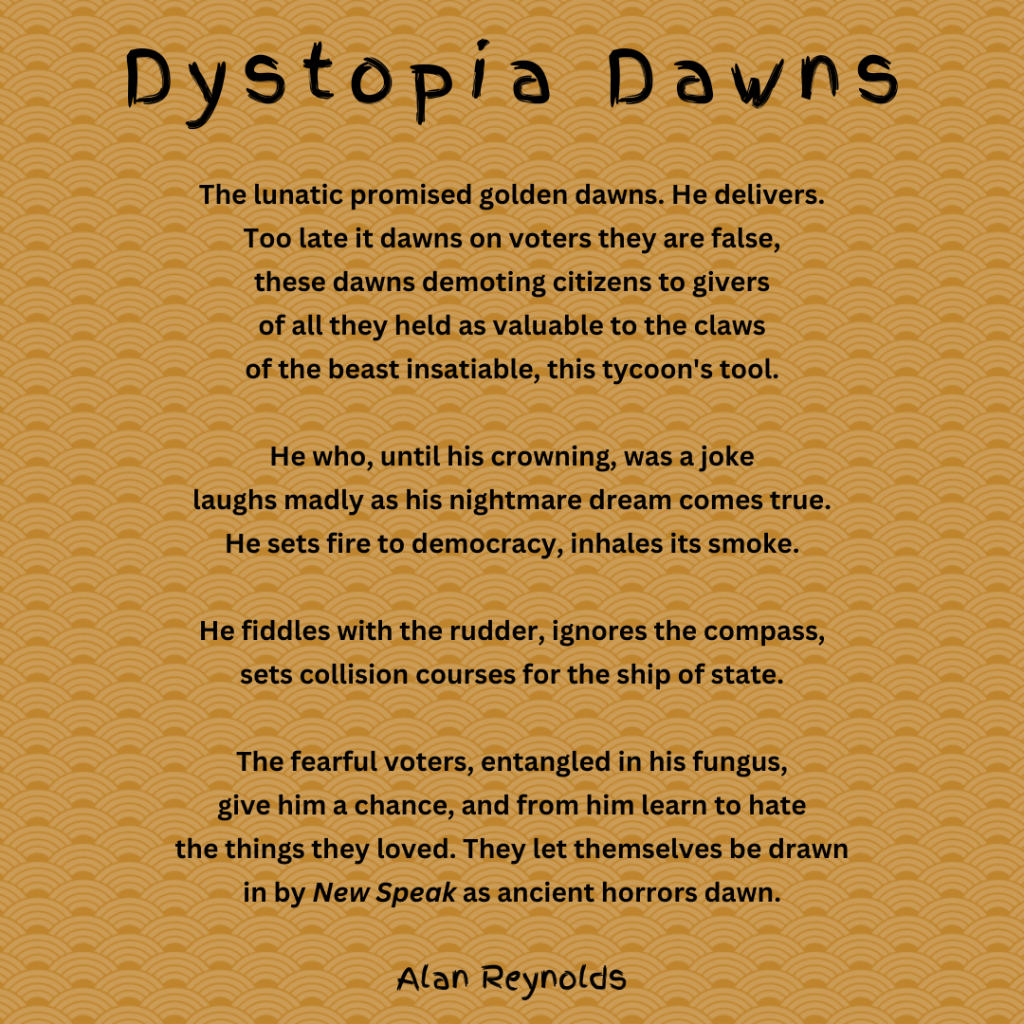

Dystopia Dawns

Image

Supply Slide

‘To stiff a virus in mid song,’

clinicians say, ‘cannot be wrong.

So by extension it is we

whose work will set the planet free.’

‘No, by best logic it is us

(your ‘we’ is twee but who’s to fuss),’

say engineers, and build a road

as killing field for cat and toad.

‘We make the vehicles, their lamps,

refueling stops, and maintenance camps

so humans can ride roughshod through

the habitat of owl and shrew.’

‘With our aid fools can forests fell,

inverting lines that used to swell

with fair-caught trout. They are no more

now we’ve made nets and heavy bore.’

‘A piece of Heaven with a beach

was not beyond our tankers’ reach.

To those who washed the birds in answer

we sent a friendly warning: cancer.’

‘No, not warn thém. They all will die.

The warning’s for their friends who cry

and for their children left alone:

the world is ours hours to own.’

Clinicians treat the engineers

for nightmare, lower-colon fears,

and for their failing faith that they are right

to hide the stars with manmade light.

These same clinicians, when they quail

at questing for the Holy Grail

of killing other forms of life

go kick a cat or take a wife

or husband as their own advisors

and when that fails, hire advertisers

to put a better spin on things

and blow expensive smoke that rings

the bug-free swamps and empty fields

with figures of fantastic yields

of crops that look superbly neat

and that sport a shelf life you can’t eat.

The advertisers takes the wages

that they are paid to serve as sages

and buy furred robots, shiny cars

and sell us colonising Mars.

Dystopia is Now

Image

‘Après Moi,’ Says the Usurper King

Image

Menelaus

I should have lied when Helen took my hand

and asked me quietly did I want to see

her room. She said her parents were away

and I said yes and followed up the stairs

and down the too-wide corridor to where

we stopped at nothing but an open door.

We stopped there too, and kissed, and time ran hot

and hurled us through the door and through the room

to stand beside the window and look out.

Look out, she said. This is my father’s realm.

It runs down to the river and beyond

those tumbling waters up that harrowed hill.

My father received this as a gift. To work.

He’s worked it up, and when he starts to tire

he’ll pass it on to me and to my man.

Are you that man? she asked. I should have lied.

Instead, I said I was and asked if this

window where we stood was of her room.

No, she said, here’s where my parents sleep.

We walked back through it then, climbed further stairs

and trailed our hands along a banister

she said the servants waxed three times a year.

We reached a landing. I reached in her dress

and she resisted after a short while

and we went further than we’d gone before

but stopped again. I tried to hide my pain

and made a joke, I don’t remember what.

Dó you, Helen asked, have rooms like this

where you live? Nó, I did not lie, we don’t.

She let me enter, shoeless. I was scared.

Scared I’d sneeze or something and she’d laugh.

Je t’adore, she said. I locked it too.

We acted like we did not hear the click.

My father’s rich, she said, are you so tired?

Come over here, let’s play like we’re asleep.

I played I had control. I tried to count

my heartbeats and not think about her breasts.

A thousand miles downstairs a ringing bell

persisted ringing every time we moved

and peacock sentries on the upper lawn

cried warnings I alone was cursed to hear.

And Helen took my hand. I almost died.

The sun came up three times in half an hour

and I learned Heaven’s not that far away.

A small cloud passed her window and returned

then fell like feathers, landed on the strip

that separates their stables from the pool.

Her father, back from Paris, looked our way

and disappeared. I heard him in the hall

and on the lower stairs and then on hers.

I hurled my clothes and shoes and then myself

out Helen’s window. On the balcony

I met her mother, massive and composed.

Son, she called me. I put on my clothes.

I work here now, for Helen, on her farm.

I have my own rooms. I don’t see her much.

The few times we pass each other I look and think

she once was pretty, on that fateful day

that she asked me up and I forgot to lie.

Shooting Star

Image

Beliefs and Creeds of Horses and of Dogs

Of the creeds of horses and beliefs of dogs,

I claim no knowing—only this:

they ponder mine as little as I ponder theirs.

Even here, in this, I am shaky, ignorant.

Knowledge, fleeting as always, escapes me now,

and the themes I grasp leave me cold in the autumn

of this perfect day, free and out of work,

not the slightest bit confused on which is which.

The waitress frees the chained-together chairs.

I choose the best chair, how we humans know

a mystery to the only other souls:

the tourist horse and the dissipated panting dog.

The others—there are no others here—

I cannot see, but I admit their presence

and fear I may in my ignorance offend them,

fumbling phrases, doubting their rite:

which serves as wafer, which as wine.

The waitress brings me fresh orange juice. I wait.

‘What heavy thoughts,’ the lying dog must think,

‘occupy the draught horse, dreaming its fly whisks,

avoiding whinnying except when part of the service.’

A man in shorts, cap, and camouflage shirt

ascends the eight, marble, steps next door

and goes inside, the horse seems sure, to hosannas.

It is early and with no custom, and the chef himself

provides me, seated outside in the best chair,

my fish and loaf while I turn at the sound of hooves

behind me, across the Prinsengracht, where barks

pursue the horse, mane damp with the city’s weight,

propelling, by pulling, a cart of intentional tourists.

A dove, conspiratorial and keen,

settles in the chair beside me, murmurs,

‘Where does all this lead?’—not kindly, but slyly.

I give him thoughtless invective, the only kind

that counts against me. Father, I have sinned.

The sun blinks out; the phantoms fold into shade.

They, the dog and the draught horse, reappear

on the tales of clouds resuming autumn coverage

of the best chair, mine. Guests arrive.

Each claims the best chair as her throne,

silent as we feast on separate truths,

while the dog and horse dream far beyond us.